On a different continent, in differing political circumstances, British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan made a historic speech, the infamous line from which can be readily ascribed to the contemporary fight against climate change and the race to reach Net Zero: ‘The wind of change is blowing through this continent, and whether we like it or not, this…is a political fact.’

The ‘wind of change’ MacMillan described was that of burgeoning national identity in the face of decolonisation, but in modern Britain the phrase can hold another meaning – the growing realisation of the imperative need to shift to low carbon renewable energy to combat climate change.

In this sense, we are very much facing a literal ‘wind of change’; as the UK reviews how it can decarbonise quickly and effectively, the significant role of offshore wind in reaching Net Zero has become increasingly apparent. It is therefore vital to assess current hurdles to offshore wind deployment, the socio-economic opportunities available, and the measures the Government is taking to retain the UK’s global leadership in offshore wind technology.

At the core of this piece are two complementary reports: Mission Zero: The Independent Review of Net Zero, by Chris Skidmore MP, the leading Conservative MP on Net Zero who signed the 2050 commitment into law in 2019; and a recently published report by Onward, a centre-right think tank with close ties to the Government, entitled Green Jobs, Red Wall.

Where the wind has blown

Since 2014, the price of UK offshore wind has fallen by a massive 70 percent and now sits below the cost of fossil fuels.[1] This effect has translated into jobs: the offshore wind industry currently employs around 31,000 people in the UK – two-thirds of which are direct jobs. These are concentrated in Scotland (30%), Yorkshire and Humber (15%) and the North West of England (9%).[2]

The prospect of greater job creation also looks positive as the Offshore Wind Industry Council predicts that the UK’s offshore wind sector will support nearly 100,000 jobs by 2030.[3] Of these jobs, shorter term opportunities will continue to emerge in construction and installation activities, whereas medium to long term careers are projected to be secured in maintenance, production and R&D. Significantly, many of the technicians and engineers required for the deployment of offshore wind are expected to be recruited from the existing oil and gas workforce, securing livelihoods in areas where fossil fuel production is historically embedded.[4]

The scale of the opportunity in offshore wind alone is staggering: an estimate by National Grid found that the energy sector will need to recruit for 400,000 jobs between now and 2050. The value of investing in offshore wind is therefore without question, but in order to harness these opportunities, greater clarity and investment is required from central government.

Where the wind will blow

The UK is unquestionably a global leader in offshore wind, but to retain this accolade, further action is required.

In recent years, the Government has taken a leading role in securing the offshore wind sector, including in 2019 when it signed the Offshore Wind Sector Deal, which saw the sector commit to increase UK manufactured content to 60% by 2030; though the target is not legally binding. The deal also saw industry agree to invest up to £250m to develop UK supply chains, increase exports fivefold to £2.6 billion by 2030, and to improve the representation of women in the workforce. In return, the Government committed to hold regular ‘Contracts for Difference’ auctions, under which offshore wind farms can obtain 15-year, fixed-price contracts for their output.[5]

Similarly, in October 2021, the Government allocated £160m of funding to companies constructing floating offshore wind ports and/or factories. A further £160m scheme to upgrade ports and infrastructure to support conventional offshore wind was also approved.[6]

Estimations on the trajectory of offshore wind power are impressive and explain why the UK’s ability to reach Net Zero will rely heavily upon the realisation of offshore wind. The Government has said it will quadruple offshore wind capacity by 2030 to reach 50GW, whereas National Grid ESO expects capacity to grow tenfold by 2050 to reach 110GW.[7] Furthermore, expectations around floating offshore wind are also high, with the British Energy Security Strategy targeting 5GW by 2030, with a potential gross value added (GVA) of £43.6 billion and 29,000 jobs.[8]

The value such proliferation could bring to the UK-wide economy is also a major impetus for growth, with export opportunities for supply chain companies. The UK is the second-largest sub-sector market for operations and maintenance, and the value of these exports is estimated to increase fivefold to £2.6 billion by 2030 as global markets grow to £30 billion per year, aided by the rapid growth of global offshore wind to reach potentially 380GW by 2030.[9]

In addition to significant economic investment, the rapid upscaling of offshore wind also presents important political considerations which both reflect and tackle the socio-economic asymmetries which exist between, and within, regions. Indeed, as Onward have pointed out, the opportunities of Net Zero provide a policy solution to the question of ‘levelling up’ the country.

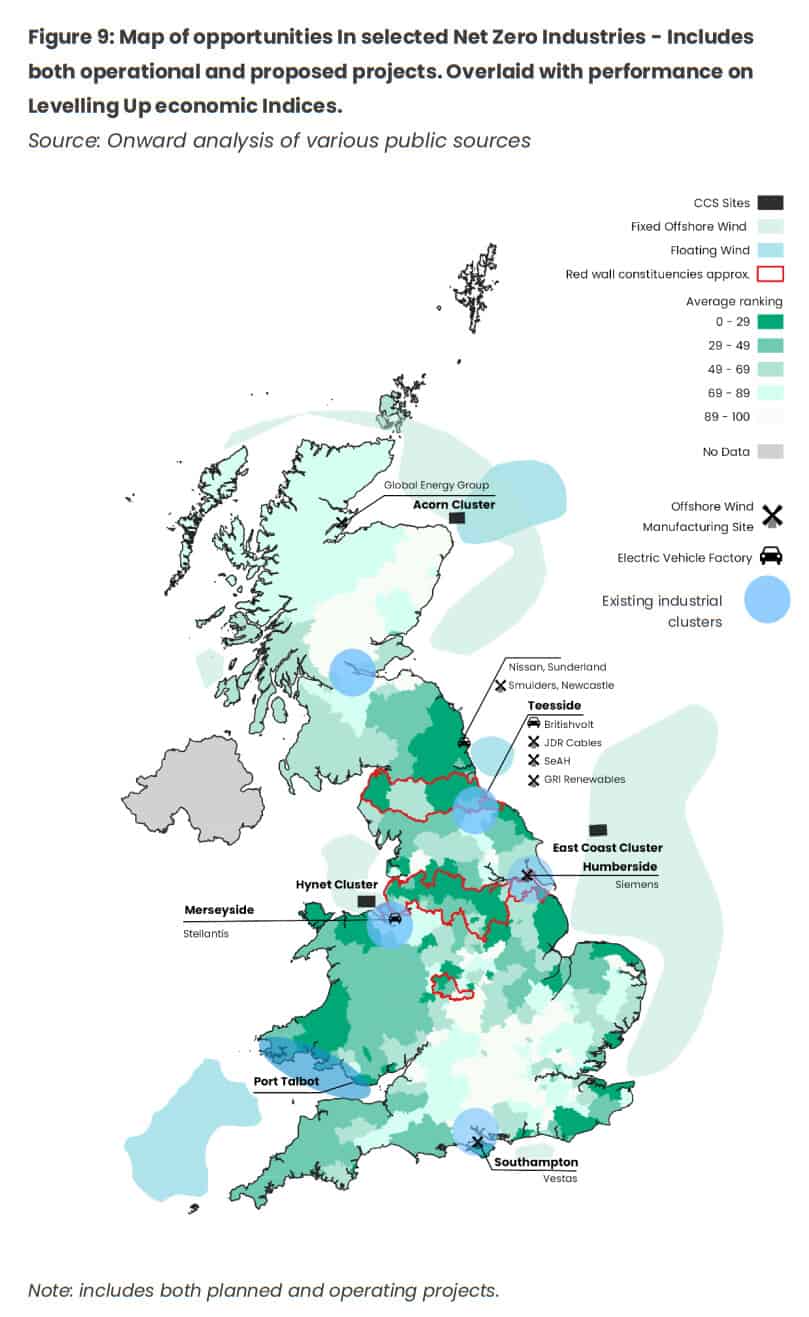

As the figure below demonstrates, areas with the potential for offshore wind deployment are already supported by a network of industrial hubs stretching from Teesside to South Wales, and from Merseyside to Humberside.[10] Onward thereby concludes that offshore wind can play a significant role in rejuvenating former heavy industry communities, particularly in the parliamentary Red Wall seats which will form the core battleground at the next election.

Indeed, the places which will host offshore wind technology and manufacturing share two common attributes: they have industrial heritage and locational advantage, the former bringing an abundance of brownfield land and skilled technical workers, whilst the latter concerns areas close to international airports with good access to electricity from nearby offshore wind farms and electricity interconnectors.[11]

Consequently, the question of offshore wind, and its vast economic potential, presents a significant opportunity for local communities to reap the benefits of the green industrial revolution.

Recommendations

It is clear, then, that action must be taken in the 2020s to secure the long-term future of offshore wind in the UK.

First, to deliver 50GW of offshore wind by 2030, the industry must deliver more than six times the amount of electricity transmission infrastructure in the next eight years than has been built in the past 30 years.[12] This will require collaboration between government and Ofgem with network companies to facilitate anticipatory investments in grid infrastructure.

Second, the UK must invest in domestic supply chains which have in the past been dominated by foreign companies – analysis by Renewable UK found that whilst 75 percent of operational expenditure went to UK companies, the proportion of capital expenditure was much lower at 29 percent.

Third, the UK must drastically increase the speed of installation rates for offshore wind farms. Onward have suggested that to meet government targets, around 4GW will need to be installed each year from 2026– four times the current rate. Crucially, the installation rate of offshore wind farms is expected to peak in the UK by the end of the decade and then remain relatively constant. The Offshore Wind Intelligence Council have forecast that UK manufacturing expenditure and capital expenditure on offshore wind farms will peak in 2029 and 2030, respectively. This means that unless factories are secured by the end of the decade, the UK economy risks losing out.[13]

Fourth, the present time taken for developers to secure planning consent is considered too long and arduous, with Renewable UK estimating that it takes 3 to 5 years to move through the consenting phase. This is attributed to the under-resourcing of planning authorities and environmental regulators, unclear guidance given to these bodies from central government, and a lack of streamlining in the process. Indeed, for the six offshore wind applications that have been processed since 2020, the average time taken for a decision to be reached was 2.5 years.[14]

Finally, the Government must provide clear guidance for offshore wind developers. It is suggested that an offshore industries integrated strategy should be released by the end of 2024 with guidance on the roles and responsibilities for the electrification of oil and gas infrastructure, how the planning and consenting regime will operate, a plan for how the system will be regulated, timetables and sequencing for the growth and construction of infrastructure, and a skills and supply chain plan for growth of the integrated industries.[15]

Conclusion: Harnessing the wind of change

In conclusion, harnessing the wind of change should not be a contentious or difficult issue: the UK is a world-leader on offshore wind and has successfully cultivated commercial partnerships over the past decade. The case for offshore wind is further justified by the investment and rejuvenation opportunities possible for communities with an industrial heritage which have been identified by the Government for growth.

The opportunity also transcends politics: the Crown Estate has just signed lease agreements with the developers of five new offshore wind farms in England and one in Wales with a collective capacity of 8GW and enough electricity to power 7 million homes. The opportunity is significant, and King Charles III has expressed his belief that the additional revenue garnered should be used for public good; a reminder that the shift to a Net Zero is as much about supporting local communities as it is about securing a sustainable economic future for the nation.

Indeed, upon assessing the scale of the task ahead, Chris Skidmore MP noted that the shift to a low carbon economy and society ‘requires not merely government to play its role, but importantly to empower the agency of regions, local communities, and individuals to play a greater role in their own net zero journey.’[16]

The wind of change is blowing across the nation; whether we choose to harness it or not, will determine the socio-economic prosperity of the UK for decades to come.

[1] Mission Zero: Independent Review of Net Zero, Chris Skidmore MP, January 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1128689/mission-zero-independent-review.pdf, p.19

[2] Onward, Green Jobs, Red Wall: How Green Industrial Jobs Can Boost Levelling Up, December 2022, https://www.ukonward.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Onward-Green-Jobs-Red-Wall-Report-1.pdf, p.44

[3] Onward, 2022, p.28.

[4] Onward, 2022, p.44.

[5] Onward, 2022, pp.64-5. Mission Zero, 2023, p.86.

[6] Onward, 2022, p.55.

[7] Onward, 2022, p.56. Mission Zero, 2023, p.74.

[8] Mission Zero, 2023, p.84.

[9] Mission Zero, 2023, p.84.

[10] Onward, 2022, Figure 9: Map of opportunities in selected Net Zero Industries – Includes both operational and proposed projects. Overlaid with performance on Levelling Up economic Indices,

(pay, productivity, employment) by local authority, p.35.

[11] Onward, 2022, p.22.

[12] Mission Zero, 2023, p.74.

[13] Onward, 2022, p.58.

[14] Mission Zero, 2023, p.87.

[15] Mission Zero, 2023, p.121.

[16] Mission Zero, 2023, p.4.